Chapter Five

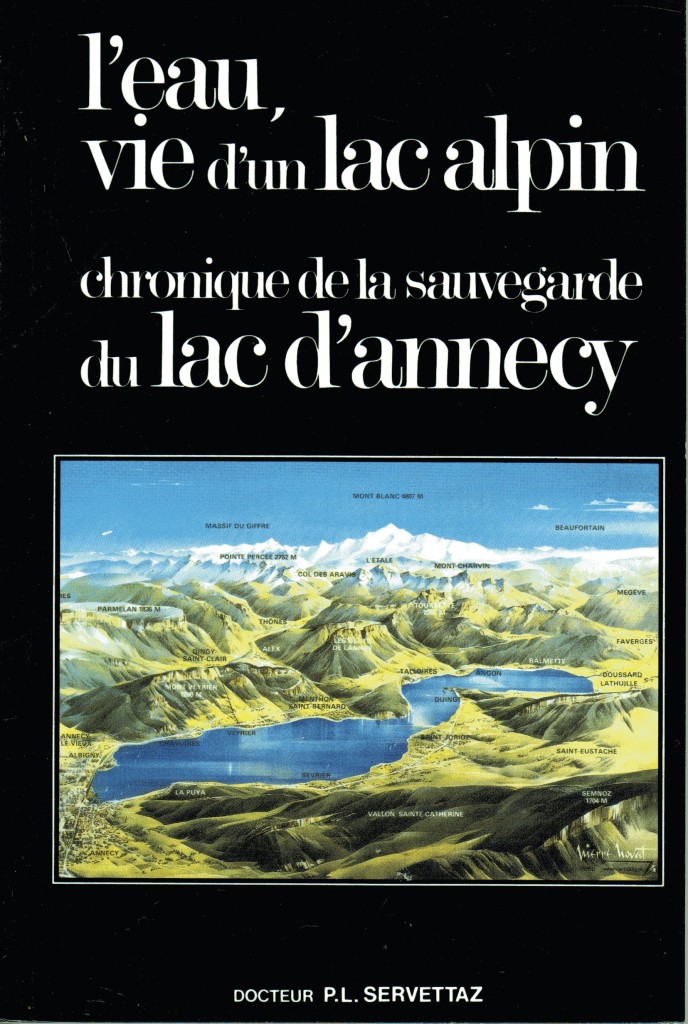

The 1977 edition - reprinted in 1991

5.1 This expanded version (referenced below as DRSZ) contains much more scientific explanation and more details of the process by which the lake was saved. The title was slightly, but significantly, revised to "l'eau, la vie d'un lac alpin". This reflects Dr. Servettaz's lifetime fascination with water in all its forms, and especially in its quintessentially beautiful manifestation, Lake Annecy.

Chapter one begins his account with a whole chapter celebrating the miraculous qualities of water.

Next he discusses mankind’s complete dependency upon water and nature in general.

His third chapter discusses how mankind’s greed, ignorance and carelessness are polluting this precious resource.

The fourth chapter discusses society’s responsibility to protect its scarce water resources.

Having dealt in general with precious water and pernicious pollution, Dr Servettaz goes on to describe the “intimate life” of Alpine lakes, detailing their physical and chemical properties and the complex web of life they contain.

Only in the sixth chapter, with all the above as background, does he begin to describe Lake Annecy specifically.

Chapter seven is described below.

Chapter eight gets to the optimistic conclusion of the story – the positive response of local politicians and the decisive action taken to safeguard the lake.

Chapter nine looks at the situation after the lake has been saved and the work that still needs to be done to ensure its protection.

Finally, chapter ten summarises the importance of the annual scientific surveys of the state of the water in lake Annecy and includes a lengthy set of appendices of documents from the time.

5.2 Much of Dr. Servettaz’s account, the physical and biological description of the lake, the science explaining the impact of pollution and the work done by SILA to solve the problem, is dealt with elsewhere on this site, if not in such detail, and does not need repeating here. But four important questions are not dealt with elsewhere:

Why was it that Dr Servettaz and not someone else took the lead?

During the years before the creation of SILA, what did his campaign involve?

How was it that this environmental campaign achieved such success, when so many others have failed?

And finally, his campaign lasted some thirty years, the first eleven before SILA was established and then another nineteen as he supported SILA’s work through to completion. What was it that gave him the energy and strength to pursue his cause with such dedication for such a long period of time?

5.3 These questions are addressed in the seventh chapter of the book, entitled “The laborious beginnings of saving the lake.” He begins with his boyhood memories. “On each holiday in Annecy-Albigny, summer or winter, I took the opportunity to steal away from my dear hospitable cousins and playmates, and go off secretly to admire the lake, and during those hours fill myself with its beauty, seeking to imprint upon my memory the prodigious spectacle it afforded from the grounds of the hotel Imperial.” (DRSZ 136)

5.5 This early love of the lake proved long lasting, and the reason why he returned there in May 1946 to work as a surgeon at the local hospital. “My whole life has been marked to this day by a great passion of admiration for this site. It partly explains my subsequent protective attitude towards it. My respect for this masterpiece of nature was entirely natural, taken for granted and without any calculation: these are the original emotional motivations for my action.” (DRSZ 136)

The Story

Chapter One. From the Times, 1977, Article by Alan McGregor. The only account of the story published in English

Chapter Two. From French Journal Clés, by Patrice van Eersel and Martine Castello. Update to the story, published July 2011.

Chapter Three. Dr Paul Louis Servettaz publishes three versions of his account.

Chapter Four. La Vie d'un lac alpin The first account of the story, 75 pages by Dr Paul Louis Servettaz published in 1971

Chapter Five: L'eau, la vie d'un lac alpin Updated version of the above with 280 pages, published in 1977, reprinted in 1991

Chapter Six: Water, the economic life of an alpine lake

5.6 It was a joy to be able to return to this peaceful life by the lake after the horror of six years of war, not least of which for him was the bombing of the nearby town of Thônes. ¹ A particular pleasure was to be able to take up his favourite sport of diving. “My sporting instincts found their expression mainly by the lake side, above and ultimately below. The quality of the water was therefore by no means a matter of indifference to me, and in my eyes, you will understand why, was of an interest equal to if not greater than the poetry which the lake inspired.” (DRSZ 138)

¹ Thônes is best known for its resistance to the Germans during World War II, organized in the valley by François de Menthon who had been revolted by the brutality towards many Savoyards during the attack upon Annecy on 2 May 1942. In February 1943, Edward Pochat organized the first maquis in mountain huts to provide refuge to young men refusing to become conscripted labour for the German war effort, under the newly introduced STO (Service de travail obligatoire) regime. During this year the maquis fought against the militia of the Vichy regime and the Italian occupation forces, particularly on June 17, 1943 at Lanfon and on August 20, 1943 at Confins. In January 31, 1944, Tom Morel camped on the plateau with 120 guerrillas, increasing by late February to around 300. On the 26th March 1944, a large scale attack involving around 10,000 men was carried out by German troops and the French militia. The numbers involved were disproportionate to the 465 maquisards on the Plateau. (National Monument to the Resistanc Plateau Glières)

On August 1, 72 allied aircraft dropped 160 tons of equipment on the plateau of Glières and in response, on August 3, the town of Thônes was bombed. At 18 hours, three German planes flew over the city and bombed the church, killing six people. An hour later, the planes returned and bombed the people clearing the damage from the first bombing. In total twelve people were killed. On August 19, 1944, the city was liberated by the Resistance. This was the first commune in France to be liberated by its own forces, thanks to the supplies dropped by the allies on August 1. On 5 November 1944, General de Gaulle visited Thônes to pay his respects at the Morette Military Cemetery which now hosts the graves of 105 resistance fighters and a museum records the resistance on the Glières plateau. (Wikipedia - French Version)

The Story

Chapter One. From the Times, 1977, Article by Alan McGregor. The only account of the story published in English

Chapter Two. From French Journal Clés, by Patrice van Eersel and Martine Castello. Update to the story, published July 2011.

Chapter Three. Dr Paul Louis Servettaz publishes three versions of his account.

Chapter Four. La Vie d'un lac alpin The first account of the story, 75 pages by Dr Paul Louis Servettaz published in 1971

Chapter Five: L'eau, la vie d'un lac alpin Updated version of the above with 280 pages, published in 1977, reprinted in 1991

Chapter Six: Water, the economic life of an alpine lake

5.7 His lifetime affection for the lake, combined with his hobby of diving, soon led his naturally curious mind to study the science of the lake. “I acquired, self-taught, some serious ecological knowledge, a certain competence in this new field of study and somewhat complementary to the ‘Certificate of study of physics, chemistry, and animal and vegetable biology’ with which medical studies began in my time. Limnology (the study of lakes) was stuttering into life in those days. I read very attentively, pen in hand, the works of the first researchers interested in the study of lakes.. Alphonse Forel, Marc le Roux, Delebecque, Legay, E. Hubault, H. Onde and B. Dussart.” (DRSZ 139)

5.8 So Dr. Servettaz turns out to be already somewhat exceptional thanks to his great passion for the lake, his diving which enabled him to see beneath a lake surface which was all his fellow citizens could see, and his self-taught expertise in the then relatively unknown science of limnology. This is then why it was that Dr. Servettaz and no-one else had the vision to see the threat to Lake Annecy and rose up to lead the campaign to save it. But what was his campaign exactly?

5.9 Chapter Seven continues to describe this campaign not so much chronologically but thematically. When he returned to Annecy in May 1946 no-one understood his point of view. “Both my old and my new relations, whether from the area or newly arrived, appeared to me totally indifferent to these problems (admittedly not yet evident but lying in wait) ignorant of the lake’s specific biological processes, and completely uninterested in the lake’s future (with the exception of which I will speak later of the remarkable leaders of the association of fishermen). Everyone believed firmly in that the lake was some kind of eternal, unchanging object – ‘it has survived since the last ice-age’, they would say, ‘it is here now and will remain unchanged till the end of time’”. (DRSZ 140)

5.10 So his first effort was to look for signs proving how the destructive treatment of the lake was causing it harm. “I searched for warning signs which could alert me and which I could use to convince the people around the lake, all of whom were entirely indifferent to the degradation in the quality of the water which they denied, saying it looked no different from the lake their fathers saw!!! Always on the look-out, forever scrounging for anomalies, I realised that I could count on no-one but myself. What an immodest pretention! What vanity! But it was the reality. I was one of the very few citizens, if not the only one, in a position to render the service of alerting the local inhabitants: I kept watch over the lake!”(DRSZ 141)

The Story

Chapter One. From the Times, 1977, Article by Alan McGregor. The only account of the story published in English

Chapter Two. From French Journal Clés, by Patrice van Eersel and Martine Castello. Update to the story, published July 2011.

Chapter Three. Dr Paul Louis Servettaz publishes three versions of his account.

Chapter Four. La Vie d'un lac alpin The first account of the story, 75 pages by Dr Paul Louis Servettaz published in 1971

Chapter Five: L'eau, la vie d'un lac alpin Updated version of the above with 280 pages, published in 1977, reprinted in 1991

Chapter Six: Water, the economic life of an alpine lake

5.11 But Dr. Servettaz was not scornful, and understood the ignorance of his ordinary fellow citizens. “It has to be said that very few people in the whole world were familiar with these problems, reserved at that time for specialists and even for them little known; a few wise men and researchers locked away in their ivory towers and tiny academic coteries at University generating work and theses, but none of them publishing (perhaps for lack of means) popular but substantial articles, so necessary for initiating and informing the public at large.” (DRSZ 142)

5.12 However, the Doctor knew of a landmark paper written in 1943 specifically referring to Lake Annecy by one E. Hubault, who wrote: 'Wastewater is discharged directly into the lake without any treatment and is giving the lake an undeniably eutrophic character, recent, newly arrived, directly caused by mankind.' "This was for anyone who knew anything about eutrophication a solemn warning, however it passed unnoticed by all who should have picked it up: the organisations responsible for taking care of the lake: the departments of Health, Bridges and Roads, Water and Forests. I had the impression of being the only one who had heard! And so, unknown to all those interested parties, a sword of Damocles had been suspended over the life and destiny of the lake, which was loved by some, and used for every conceivable end and exploited by others.” (DRSZ 143)

5.13 It is worth noting at this point that despite the many similarities between the stories of Lake Annecy and Lake Washington, here is one big difference. Dr. Servettaz’s counterpart W. T. Edmondson, the person who articulated to the people of Seattle what dangers the lake faced, was a University zoologist charged with carrying out scientific experiments. So the story of Lake Washington begins with scientific evidence produced by an acknowledged (except by his opponents!) expert. Dr. Servettaz was an ordinary citizen, lacking the formal credibility of scientific research. All he had was his self-taught knowledge and his passion for the lake. Dr. Servettaz’s challenge as an ordinary citizen was to raise awareness amongst an ignorant citizenry and local administration – Dr. Edmondson’s challenge as an expert scientist was to overcome sophisticated opposition financed by big business. So the subject matter of the battles were similar, and the outcomes similarly spectacularly successful, but the nature of the campaigns were entirely different. With one exception – the way the campaigns were conducted and the personalities of the campaigners.

The Story

Chapter One. From the Times, 1977, Article by Alan McGregor. The only account of the story published in English

Chapter Two. From French Journal Clés, by Patrice van Eersel and Martine Castello. Update to the story, published July 2011.

Chapter Three. Dr Paul Louis Servettaz publishes three versions of his account.

Chapter Four. La Vie d'un lac alpin The first account of the story, 75 pages by Dr Paul Louis Servettaz published in 1971

Chapter Five: L'eau, la vie d'un lac alpin Updated version of the above with 280 pages, published in 1977, reprinted in 1991

Chapter Six: Water, the economic life of an alpine lake

5.14 Dr. Servettaz was also sensitive to what we can term the Environmentalist’s Catch 22. On the one hand his love of the lake and his community drove him to draw attention to each and every disgusting example of the way the lake was currently being abused, not just by the discharge of untreated sewage, but by the dumping of every conceivable kind of rubbish. On the other hand he did not want to upset his fellow citizens, particularly those working hard to promote the lake as a clean, safe and attractive place for tourists to visit. He had to tread a fine line. “Without provoking, courteously, I spread the word of my anxieties which many asked me to keep to myself. From time to time certain opponents threatened me and insulted me, although they were wasting their efforts since I was indifferent to blackmail or fear. I followed my fixed idea, very firmly, trying not to panic those I spoke to from time to time whom I desired to see convinced step by step, conscious that the fight would become more intense as, to my eyes, the situation was becoming worse day by day.” (DRSZ 146)

5.15 After two years of individual conversations and speechmaking as an individual, the Doctor moves his campaign into second gear after he realises that if anything is to be done he needs to convince the locally elected representatives – the ‘Elus’. Consequently, in 1948 he got himself elected one of several assistant mayors to the town of Annecy. “My colleagues soon discovered what certain among them were to call with a grin ‘my obsession with the lake’ and without taking me in any way seriously, were amazed at the importance I attached to this ‘idee-fixe’ – for them too original, completely futile and unnecessary! It was not of little interest to me that among all the subtle arguments of all the different political parties’ campaign leaflets there was never any mention of the future of the lake.” However, while this may have been true of many of Dr. Servettaz's colleagues at this time, one of them was quickly persuaded of his concerns, and fortunately this was the most important person of them all: Charles Bosson, the new mayor of Annecy. (DRSZ 147)

5.16 The first opportunity he had to raise his concerns at this new political level was when the renovation of the water treatment plant at la Puya in Annecy came up for discussion. He pointed out that the dirty condition of the water was placing an excessive burden on the treatment plant, clogging up its filter and requiring huge sterilization efforts to clean out the bacteria in the water. “In conclusion, I advanced the idea that a programme to clean up the lake would be economical and should go hand in hand with the refurbishment of the water treatment plant. They laughed at me…” (DRSZ 148)

The Story

Chapter One. From the Times, 1977, Article by Alan McGregor. The only account of the story published in English

Chapter Two. From French Journal Clés, by Patrice van Eersel and Martine Castello. Update to the story, published July 2011.

Chapter Three. Dr Paul Louis Servettaz publishes three versions of his account.

Chapter Four. La Vie d'un lac alpin The first account of the story, 75 pages by Dr Paul Louis Servettaz published in 1971

Chapter Five: L'eau, la vie d'un lac alpin Updated version of the above with 280 pages, published in 1977, reprinted in 1991

Chapter Six: Water, the economic life of an alpine lake

5.17 This discussion led Dr. Servettaz to focus on the threat from bacteria in the lake. As a hospital doctor he was dealing with the threat of polio, one of the major diseases of the twentieth century. At that time there was no vaccine for this disease which paralysed young children. (The first vaccine was developed in the 1950s by Jonas Salk.) The idea that young children were swimming in poliomyelite-infected bathing areas around the lake at Petit Port and Marquisats, made his blood run cold. He was also horrified at the thought of all the newly established camping facilities around the lake, ill-equipped with toilet facilities, where the reed beds were used as latrines. He collected paperwork documenting case after case justifying his concerns, and continued to raise them in all his public and private conversations as a deputy mayor.

5.18 But still, in 1950, he was at a loss for how to break through the 'wall of ignorance'. So he took his campaign to a third, more public level. He looked to recruit allies to his cause, such as local fishermen, other users of the lake for recreation, and some teachers of natural history. The snowball began to roll. He recalls amongst other scandals one fine autumn afternoon when a pestilential odour in the reed-beds around the Bout-du-Lac led to the discovery of a huge pile of rotting carcasses dumped there by a reckless butcher. “That was no longer tolerable, and it seemed to me better to alert the public, spread the word to journalists, and expose the truth, even if the result for a time was to besmirch our trade-mark image (could this put a brake on tourism?) in support of which a very skilful tourist propaganda always hid the sad and rude realities.” (DRSZ 151)

5.19 He then decides on a fourth level: to set up a diving club – ‘The Alpine Subacquatic club’ - to explore sights never seen by any local citizen, the floor of the lake. The specific intention was to carry out an inventory of all the rubbish that had been dumped in the lake over the years. The divers couldn't believe what they found. “Our anger was only matched by our sadness and disgust.. This hotel had used the lake as a rubbish tip and dumped old bedframes into it. Another, on the occasion of its refurbishment, had dumped all its old toilets, broken bidets, rubble with bits of old-fashioned carpet showing, and discarded documents from 1920.. Not far from the surface, to irrigate all the rubbish below, the outlets of a series of sewage pipes emptied the content of kitchens and fifty toilets.” (DRSZ 152)

The Story

Chapter One. From the Times, 1977, Article by Alan McGregor. The only account of the story published in English

Chapter Two. From French Journal Clés, by Patrice van Eersel and Martine Castello. Update to the story, published July 2011.

Chapter Three. Dr Paul Louis Servettaz publishes three versions of his account.

Chapter Four. La Vie d'un lac alpin The first account of the story, 75 pages by Dr Paul Louis Servettaz published in 1971

Chapter Five: L'eau, la vie d'un lac alpin Updated version of the above with 280 pages, published in 1977, reprinted in 1991

Chapter Six: Water, the economic life of an alpine lake

5.20 “To convince you of the normal mentality of those times, I will tell you that at the Liberation several big 500 kg bombs (non explosive following the destruction of the SRO factory Schmidt - since become the SNR ball-bearing factory) were thrown into the lake (after being defused) just in front of the bay at la Puya.”

5.21 Perhaps the Subacqua club's most dramatic episode was at the Hotel Imperial. And it is a drama of grand proportions. Dr. Servettaz had very good relations with the director of the hotel, Mme Dulong, and in fact owed her the greatest debt of gratitude there is – she saved his life. At 7 am on the morning of 22 July 1944, shortly before the liberation of Annecy, an annex of the hotel “villa Schmidt” was occupied by the Gestapo who were planning their desperate counter-measures against the tide of resistance which was rising every day. Mme Dulong overheard a conversation between the Gestapo’s inspector-executioners and their superior officers. They told him of their intention to interrogate as a matter of urgency four doctors, an architect, and a woman, whose names were set out in a list on a napkin by the side of a flask of coffee. Mme Dulong saw the list and alerted as many of those on it as she could. All managed to escape except one doctor Hubert Laurent whom Dr Servettaz had invited to Annecy from Lyon. Laurent was tortured horribly at villa Schmidt and then machine-gunned on the afternoon of 16 August 1944 with three other members of the resistance.

5.22 And so with this huge debt of gratitude, Dr. Servettaz had to tackle Mme Dulong about the issue of her hotel’s sewage pipes emptying their waste right next to children’s bathing areas. “What a debt of gratitude I owed to Mme Dulong! I relived this tragic episode each year with each examination of the severe bacteriological infection which was threatening the lives of innocent bathers; it was for me a painful crisis of conscience.” But enough was enough. “One evening, on the 10 September 1965, I decided, with a heavy heart, on ‘operation commando’ a project long in the making. I went on a dive and secretly blocked up – hermetically sealed - the slimy orifice of the hotel’s underwater sewage pipe with three 2 kilo sacks of quick-drying cement. It was not an act of which I was proud, but it was effective. The following season, it turned out, was much more satisfactory in terms of security for bathers. I acknowledged my action knowing the disastrous consequences (the overflowing of all the toilets in the hotel) for a ‘noble’ client.” (DRSZ 157) Despite fully owning up to this act, Dr. Servettaz was never prosecuted and the hotel connected its sewage pipes to the municipal system the next year.

The Story

Chapter One. From the Times, 1977, Article by Alan McGregor. The only account of the story published in English

Chapter Two. From French Journal Clés, by Patrice van Eersel and Martine Castello. Update to the story, published July 2011.

Chapter Three. Dr Paul Louis Servettaz publishes three versions of his account.

Chapter Four. La Vie d'un lac alpin The first account of the story, 75 pages by Dr Paul Louis Servettaz published in 1971

Chapter Five: L'eau, la vie d'un lac alpin Updated version of the above with 280 pages, published in 1977, reprinted in 1991

Chapter Six: Water, the economic life of an alpine lake

5.23 But this was in the future. Back in the early 1950s Dr Servettaz was still wondering what he had to do to raise public awareness. And this brought him to the fifth level of his campaign – assembling as much scientific evidence as possible from biological surveys of the lake water. He had even paid for the first of these himself and later shared the cost with the local administration once elected deputy mayor. The time had come for hard facts, research and science to convince the people.

5.24 The first research reports came from the society of fisherman. Although their concern was more for the quality of their fishing than the quality of the lake’s water, there was a mutual interest with Dr. Servettaz’s campaign. They produced factual reports annually documenting the fall in catch of noble fish. This seemed to proceed in step with the deoxygenation of the lower depths of the lake. This was the result of increased algae growth, because when algae died and sank through the lake it was consumed by bacteria, using up dissolved oxygen in the process. Dr. Servettaz was invited to speak as an expert witness at the fishermen’s meetings – playing a role similar to that of Dr. Edmondson in Seattle just a few years later. “In them I truly found a quality audience, receptive, readily accessible to scientifique information, listening well to the detailed explanations I gave. Their questions were always very pertinent! They became trusted collaborators, committed to supporting a long lasting campaign.” (DRSZ 162) In particular the fisherman’s society was fortunate enough to have at its head one Louis Blanc who gave great support to the campaign. Dr. Servettaz was alone no longer. And so he stepped up the campaign up to yet another level. “I made exposés, spoke at conferences, wrote articles for the daily press and monthly journals, .. attended meetings of societies and clubs, speaking on a theme with which I had by now been identified.”(DRSZ 166)

5.25 Besides the fishermen's studies and Dr. Servettaz’s own reports, there were other sources of scientific research. It turns out that after Dr. Servettaz had raised the issue as assistant mayor in May 1948 the Superior Council for Hygiene of France had urged the Ministry of Reconstruction to instruct the Bridges and Roads department (led by chief engineer M. Fumet, and engineer M. Hudry) to study the cleanliness of the drinking water, the way the communes around the lake treated their waste water, and above all the ability of the lake to clean itself. This work was eventually carried out in two steps in 1951 and 1954 with the assistance of INRA at Thonon. Further, in 1952, a Miss Suchet produced a report on oxygen deficiency in the lake. There was also a report by the Water and Forests department on the algae causing eutrophication. Each of these reports was limited and disconnected, but by the mid 1950s the weight of all this evidence was beginning to change opinions.

The Story

Chapter One. From the Times, 1977, Article by Alan McGregor. The only account of the story published in English

Chapter Two. From French Journal Clés, by Patrice van Eersel and Martine Castello. Update to the story, published July 2011.

Chapter Three. Dr Paul Louis Servettaz publishes three versions of his account.

Chapter Four. La Vie d'un lac alpin The first account of the story, 75 pages by Dr Paul Louis Servettaz published in 1971

Chapter Five: L'eau, la vie d'un lac alpin Updated version of the above with 280 pages, published in 1977, reprinted in 1991

Chapter Six: Water, the economic life of an alpine lake

5.26 A full two years later the decision was taken by the mayors of communes around the lake to set up the Syndicate Intercommunal of Lake Annecy, the organization empowered to carry out this work. But what is the answer to the final question? How come Dr. Servettaz was successful in his campaign when so many others have failed? Here it is instructive to make a useful, if somewhat unexpected, comparison.

5.27 Henrik Ibsen wrote ‘The enemy of the people’ some fifty years before our story. It was about an eminent local doctor (Dr. Stockman) who suspects that the water in the town’s public baths has become contaminated and decides to launch a campaign to raise awareness of this issue among the local population.

5.28 He receives a letter with a report confirming his suspicions about the contamination and agrees with the editor of the local newspaper to have an article printed, even though it might damage the reputation of the town and lead to the closure of the baths. He believes he is the saviour of the town.

5.29 However, very much unlike mayor Charles Bosson, the local mayor Peter visits Dr. Stockman and accuses him of being selfish and not thinking of the big picture, the damage to the town’s reputation and economy. He encourages Dr. Stockman to retract the article and deal with the problem in a quieter way. But Dr. Stockman refuses and determines to press ahead with the article.

5.30 The next day however, the newspaper has a change of heart about attacking the reputation of the town and refuses to print the article. Out of desperation, Dr. Stockmann decides he doesn't need the paper and he can fight this battle on his own, by instead calling a town meeting to spread the information.

5.31 When Stockmann finally gets a chance to speak at the meeting, he talks about the contamination of the water but also criticizes the town’s leaders and how they are the ones who know what is going on. He talks about the need for the people to be educated and about corruption. The town feels insulted by these accusations and anger starts growing in the room. By the end of the meeting the town has rebelled as a mob against Dr. Stockmann and has marked him as an enemy of the people. Dr. Stockmann is exiled from the town.

The Story

Chapter One. From the Times, 1977, Article by Alan McGregor. The only account of the story published in English

Chapter Two. From French Journal Clés, by Patrice van Eersel and Martine Castello. Update to the story, published July 2011.

Chapter Three. Dr Paul Louis Servettaz publishes three versions of his account.

Chapter Four. La Vie d'un lac alpin The first account of the story, 75 pages by Dr Paul Louis Servettaz published in 1971

Chapter Five: L'eau, la vie d'un lac alpin Updated version of the above with 280 pages, published in 1977, reprinted in 1991

Chapter Six: Water, the economic life of an alpine lake

5.32 Dr. Servettaz conducted his campaign entirely differently to Dr. Stockman.

He educated himself thoroughly on the issue. Through copious reading and dedicated self teaching he made himself an expert in the then hardly known science of limnology.

He was patient, but at the same time absolutely determined. His campaign took more than seven years before he finally obtained official support.

He was flexible. He approached his campaign not with one sledgehammer effort, but in a multitude of ways: conversations with individuals at all levels of society, speeches at clubs and societies, publication of ad hoc articles on pollution, paying out of his own pocket for bacteriological studies of the lake water, getting himself elected deputy mayor responsible for health matters and participating in debates on the modernisation of the water works, and writing letters to the responsible government bodies.

He did not patronise his fellow citizens. Although he had educated himself in the science of limnology, which was crucial to understand what was happening to the lake, he understood that at that time hardly anyone in the world was familiar with such issues.

He was always courteous in conversation, using humour and charm, and knew when to push and when to withdraw without offending people.

He formed alliances wherever he could. He worked with the local fishermen’s association, and with individual sympathisers, such as teachers and then later, decisively with the newly elected mayor Charles Bosson.

He pursued extreme actions only as a very last resort, with a heavy heart and no pride. This was best illustrated by his description of how he blocked up the sewer outlet of the Hotel Imperial.

The Story

Chapter One. From the Times, 1977, Article by Alan McGregor. The only account of the story published in English

Chapter Two. From French Journal Clés, by Patrice van Eersel and Martine Castello. Update to the story, published July 2011.

Chapter Three. Dr Paul Louis Servettaz publishes three versions of his account.

Chapter Four. La Vie d'un lac alpin The first account of the story, 75 pages by Dr Paul Louis Servettaz published in 1971

Chapter Five: L'eau, la vie d'un lac alpin Updated version of the above with 280 pages, published in 1977, reprinted in 1991

Chapter Six: Water, the economic life of an alpine lake

5.33 And so we have the answer to our third question – how was it that Dr. Servettaz was so successful in his campaign. To be fair the character of Dr. Servettaz and the way he conducted his campaign is only part of the picture. Without the support of the new and highly capable mayor Charles Bosson his efforts may still have been in vain. Without the eventual backing of Paul Vivier and the key state departments of Health, and Bridges and Roads, and Water and Forests, such a huge project could not have been undertaken. And without the post war spirit of cooperation between the mayors of the villages around the lake SILA may never have been established to carry out the work.

5.34 Finally, from where did Dr. Servettaz get his mental energy and moral strength to sustain him through the long years of this campaign? Dr. Servettaz was a trained doctor but was also a man of passion and poetic sensibility. He was in equal measures a scientist and an artist. He taught himself the latest developments the science of Nature, but at the same time was deeply appreciative of the beauty of Nature. His vision brought together these two great currents of the environmental movement, which had been developing since the time of Copernicus, into a powerful fusion which drove him, together with his good friend Charles Boston, to pioneer a great work of environmental protection.

5.35 “The gradual raising of public awareness of the beauty of Lake Annecy is a definitive episode in the story of human interaction with the environment. The formidable challenge undertaken by our predecessors – inspired by Paul-Louis Servettaz and Charles Bosson – to save a dying lake is an outstanding example of a pioneering environment action.” Jean-Luc Rigaut, Mayor of Annecy (2008 - present), preface to “Histoires d’Eaux”, a book written by Marie-Claude Rayssac to celebrate the history of Lake Annecy, available in French at the Annecy Municipal Archives.

5.36 Having first fought for nearly a decade to persuade the citizens of Annecy of the danger to the lake, and then for more than a decade to help implement a solution, Dr. Servettaz continued to work energetically at the end of his career to publicize what had been achieved there. "In 1970,1972,1974 I gave long accounts of the life of lakes, and the measures taken to protect the one at Annecy." (DRSZ 206) Official recognition was soon to follow.

The Story

Chapter One. From the Times, 1977, Article by Alan McGregor. The only account of the story published in English

Chapter Two. From French Journal Clés, by Patrice van Eersel and Martine Castello. Update to the story, published July 2011.

Chapter Three. Dr Paul Louis Servettaz publishes three versions of his account.

Chapter Four. La Vie d'un lac alpin The first account of the story, 75 pages by Dr Paul Louis Servettaz published in 1971

Chapter Five: L'eau, la vie d'un lac alpin Updated version of the above with 280 pages, published in 1977, reprinted in 1991

Chapter Six: Water, the economic life of an alpine lake

5.37 On 2 July 1971 Minister R. Poujade, visited Annecy at the invitation of Mayor Charles Bosson to open an exhibition called "Water and Pure Lakes". This was one of the very first official visits made by France's first ever Minister for the Environment and served as official confirmation of the significance of what had been achieved at Lake Annecy. His visit led to a great deal of positive publicity in the local and national press about the 'miracle' achieved at Lake Annecy - although Dr. Servettaz reminds us it was no miracle, just a huge amount of hard work. (DRSZ 208).

5.38 On 11 February 1972, Pierre Moorgat, a french cultural attaché in Turin and old friend of Dr Servettaz, wrote to the mayor of Annecy to gather all the information he could about the campaign to save the lake in order to compile a report to be submitted to the Goethe Foundation in Hamburg. On 5 October 1972 their first ever European Environmental Prize was awarded by His Highness Count Lennart Bernadotte for the achievement of saving Lake Annecy from pollution. (DRSZ 209) It was awarded not to Dr. Servettaz, but to his long term colleague and friend Charles Bosson who had served as Mayor of Annecy from 1954 to 1975, covering the entirety of the period during which this huge endeavour was carried out and without whose constant oversight for all those years the project may well never have succeeded. Just as at Lake Washington the two key figures were the scientist, W. T. Edmondson, and the administrator, James R. Ellis, so at Lake Annecy we have Dr. Servettaz, the voice of science, and Charles Bosson, the administrator who saw that things got done.

5.39 On 15 August 1973 Robert Muller, the General Secretary of the United Nations, wrote a personal letter to Dr. Servettaz, as follows: [DRSZ 206]

"Your book reflects the three secrets of success: love, solidarity, and a clear vision for the future. If only you knew how much these three precepts are also the key to success in the great affairs of the world. Love for our planet is insufficient. Solidarity between nations is insufficient, and instead of a vision for the future, governments have their noses in their petty interests and the details of everyday life. My dream would be that the United Nations would soon become the International Syndicate of the Communities of Planet Earth, in the image of the Intercommunal Syndicate of the Communes of Lake Annecy [i.e. SILA]. We are getting there little by little but at a pace too slow to be able to confront the global problems that overwhelm us and will one day end up affecting every last individual on the planet. The success of Annecy is a source of inspiration and emulation and I will endeavor to make it known to a circle as wide as possible"

The Story

Chapter One. From the Times, 1977, Article by Alan McGregor. The only account of the story published in English

Chapter Two. From French Journal Clés, by Patrice van Eersel and Martine Castello. Update to the story, published July 2011.

Chapter Three. Dr Paul Louis Servettaz publishes three versions of his account.

Chapter Four. La Vie d'un lac alpin The first account of the story, 75 pages by Dr Paul Louis Servettaz published in 1971

Chapter Five: L'eau, la vie d'un lac alpin Updated version of the above with 280 pages, published in 1977, reprinted in 1991

Chapter Six: Water, the economic life of an alpine lake

5.40 In July 1976 Jacques Chirac, the prime minister of France, hailed Annecy's achievement with the following words, which could not have summed up the situation better had Dr Servettaz written them himself. (DRSZ 210)

"The protection of sites of natural beauty is the second essential element of a political agenda for improving the quality of life. On this matter I can say without flattery that Haute-Savoie can serve as a reference point. What was accomplished at Annecy, remains an example to us all. The recovery of the lake and its transparency cannot fail to amaze even the most sceptical. The educational value of this beautiful scene seems to me even more important, because it is enough simply to visit the shore of this lake, saved from pollution, to be persuaded that the theme "ecology" is not just an excuse for endless debate without action. Practical success is possible. Certainly it has to be earned, and I do not under-estimate the courage, the perseverance, and the spirit of cooperation which was necessary from a variety of local groups determined to achieve their goal. But in the end the proof is there."

5.41 The last words go to Dr. Servettaz himself. (DRSZ 221)

"I wish to pay tribute to all those involved in seeing through this exceptional endeavour, the first in Europe (an identical system encircles Lake Washington near to Seattle in the USA), and long before the mobilization of a global movement for the protection of the environment. The communities around the lake, conscious of their duties and interests, responded with approval and support when we raised the alarm. But this was more than a testimony of solidarity and civic duty. It was in reality a gesture of the peoples' love for the region which had seen them born or welcomed them into its magnificent landscape."

The Story

Chapter One. From the Times, 1977, Article by Alan McGregor. The only account of the story published in English

Chapter Two. From French Journal Clés, by Patrice van Eersel and Martine Castello. Update to the story, published July 2011.

Chapter Three. Dr Paul Louis Servettaz publishes three versions of his account.

Chapter Four. La Vie d'un lac alpin The first account of the story, 75 pages by Dr Paul Louis Servettaz published in 1971

Chapter Five: L'eau, la vie d'un lac alpin Updated version of the above with 280 pages, published in 1977, reprinted in 1991

Chapter Six: Water, the economic life of an alpine lake