Lake Washington Story

Lake Washington is ten thousand kilometres and halfway around the world from Lake Annecy....

yet the stories of how these lakes were saved from pollution bear an astonishing resemblance.

They are two twin pillars of the modern environmental movement

The first significant, successful, comprehensive environmental campaigns in history¹

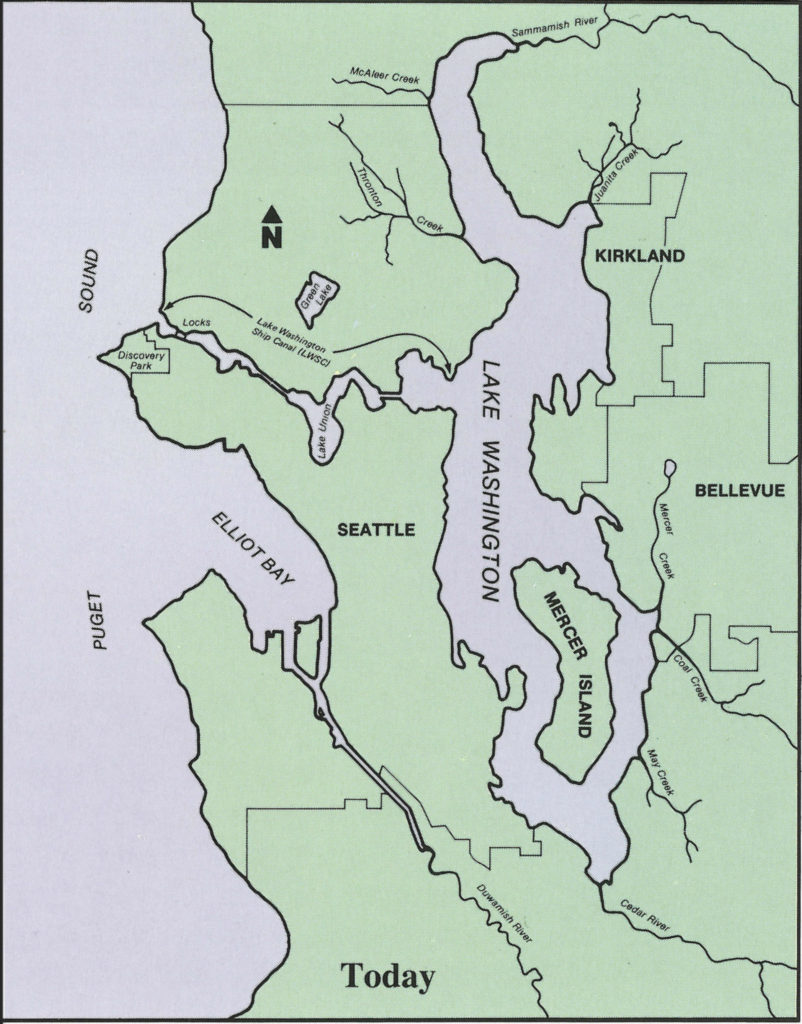

Lake Annecy and Lake Washington are both are sizeable lakes in scenic mountain settings, home to a thriving town and surrounded by an ever expanding lakeside community.

They both experienced the damage caused when sewage produced by this increasing urban population entered the lake and unbalanced a biological equilibrium evolved over millenia. These were the first two lakes in the world where the problem of eutrophication was successfully identified and managed. In both cases this was the result not of government intervention from on high but of local grassroots action inspired by the vision of a handful of well-informed, courageous and dedicated concerned citizens. In both cases an unprecedented political arrangement had to be made to get all the lakeside communities working together to solve the problem and in both cases the solution involved the largest and most expensive environmental investment made to date in their respective countries. And in both cases the results of their action were outstandingly successful, so that generations to come are able to appreciate the fruits of their labours.

The story of Lake Washington, unlike that of Lake Annecy, is well documented in English. Chapter One begins with the story as set out on the website of King County, the local authority now responsible for managing the lake, as well as carrying out a wide range of services for a community of over 2 million citizens. (By contract SILA, the authority which manages Lake Annecy, serves a community of around 250,000 and is focused solely on managing the lake). Chapter Two is an outline of the story from the point of view of one scientist J. T. Lehman. Chapter Three continues with J. T. Lehman, and his case study of the story. Chapter Four introduces the most detailed account of the story, a fine book entitled "The Uses of Ecology" written by W. T. Edmondson the scientist who played the key role in providing reliable information to the campaign to save the lake. Chapter Five is the inside story of the creation of Metro, the innovative political association of local authorities put together to solve the pollution problem. Metro is the direct equivalent of SILA in France, and their stories have many similarities, and some intriguing differences. Chapter Six is an article from the local newspaper, the Seattle Times, just a few years ago, celebrating the work of Jim Ellis, one of the key figures in the campaign to save Lake Washington. Finally Chapter Seven brings us up to date with Lake Washington today, and gives an insight into the extensive work being done every year to continue the work set in motion all those years ago.

¹First significant, successful, comprehensive, environmental campaigns

This is a bold assertion, not least coming from an author who is neither an environmentalist, nor limnnologist, nor historian, nor journalist. It is based on the following reasoning.

These environmental campaigns were significant not only for the amount of money they cost (in each case the most expensive environmental investment to date in their respective countries) but also because of the size of the populations they served and the innovation in political organisation required to effect the work, namely the creation of Metro and SILA. The success of the campaigns has been not only acclaimed for the last fifty years by the local communities fortunate enough to have benefited from them, but also cited in scientific literature throughout the world as the problem of eutrophication has gradually become understood to be one of the major threats to global freshwater resources. These campaigns were comprehensive in that they addressed each of the five fundamental aspects of environmental action: they secured the sustainability of the lakes as a source of fresh drinking water, they reduced pollution of the local environment, they ensured the health and safety of those who used the lake for recreation, they protected the beauty of the natural environment and they secured and improved access to this beauty for the population at large. And these were environmental campaigns where local citizens raised the alarm and pressed for action, because the issue of lake pollution from sewage discharge was largely unknown at the time and so not within the sphere of routine government decision making about infrastructural investment.

By contrast the construction of just about any major urban sewage system could be classified as an environmental investment, and great works such as those of Haussmann and Belgrand in Paris would be good examples. And there are interesting histories preceding our story to be written about citizens' campaigns waged to compel reluctant local administrations to build what was necessary. For instance, "on at least two occasions in the late 1700s, Paris refused to build an updated water system that scientists had studied. Women were actually carrying water from the river Seine to their residences in buckets. Voltaire wrote about it, saying that they "will not begrudge money for a Comic Opera, but will complain about building aqueducts worthy of Augustus". Louis Pasteur himself lost three children to typhoid." (Wikipedia) But installing such sewage systems addressed just one environmental issue (crucial though it was): health and safety of citizens. And for centuries the need for them had not been a subject of scientific uncertainty. The question was not if, but when, to install them.

Lake Washington Story

Introduction

Chapter One: From the King County website

Chapter Two: Battle to Save Lake Washington - an outline by J T Lehman

Chapter Three: Lake Washington Case Study - J T Lehman

Chapter Four: The Uses of Ecology, Lake Washington and beyond, by W T Edmondson

Chapter Five: The Story of Metro, by Bob Lane

Chapter Six: Will the next Jim Ellis please step forward? by Thanh Tan

Chapter Seven: Lake Washington today, back to King County website

Also, by contrast, there have been a number of significant environmental campaigns preceding our story which have contributed to laying the foundation of the modern environmental movement. Not least was John Muir's campaign in the US to establish Yosemite as a nature reserve protecting large tracts of beautiful landscape from the depredations of urban development or industrial exploitation. "In 1889, Muir took Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of Century Magazine, to Tuolumne Meadows so he could see how sheep were damaging the land. Muir convinced Johnson that the area could only be saved if it was incorporated into a national park. Johnson’s publication of Muir’s exposés sparked a bill in the U.S. Congress that proposed creating a new federally administered park surrounding the old Yosemite Grant. Yosemite National Park became a reality in 1890." (US National Park Service) John Muir was a remarkable individual who led a grassroots campaign and won over converts by celebrating the spiritual effects of the beauty of natural landscapes long before Dr. Servettaz spoke and wrote his praise for lake Annecy. However, his campaign addressed just one environmental issue (crucial though it was): protecting the beauty of the natural environment from industrial encroachment.

John Muir also founded the Sierra Club. "Founded by legendary conservationist John Muir in 1892, the Sierra Club is now the nation's largest and most influential grassroots environmental organization - with more than two million members and supporters. Our successes range from protecting millions of acres of wilderness to helping pass the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and Endangered Species Act. More recently, we've made history by leading the charge to move away from the dirty fossil fuels that cause climate disruption and toward a clean energy economy." (Sierra Club website). And it was from the Sierra Club, in the late 1960s amidst demonstrations in the US against the testing and development of nuclear weapons, that founders of two of the world's largest environmental campaigning organisations came, Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace. "Friends of the Earth was founded in 1969 as an anti-nuclear group by Robert O Anderson who contributed $200,000 in personal funds and David Brower, Donald Aitken and Jerry Mander after Brower's split with the Sierra Club." (Wikipedia). Greenpeace was founded by, amongst many others, former members of Sierra Club. "The U.S. announced they would detonate a bomb five times more powerful than the first one. Among the opposers were Jim Bohlen, a veteran who had served in the U.S. Navy, and Irving Stowe and Dorothy Stowe, who had recently become Quakers. As members of the Sierra Club Canada, they were frustrated by the lack of action by the organization." (Wikipedia) These three organisations have led significant environmental campaigns around a wide range of issues, but these take place many years after our story.

Lake Washington Story

Introduction

Chapter One: From the King County website

Chapter Two: Battle to Save Lake Washington - an outline by J T Lehman

Chapter Three: Lake Washington Case Study - J T Lehman

Chapter Four: The Uses of Ecology, Lake Washington and beyond, by W T Edmondson

Chapter Five: The Story of Metro, by Bob Lane

Chapter Six: Will the next Jim Ellis please step forward? by Thanh Tan

Chapter Seven: Lake Washington today, back to King County website

John Muir's example further inspired the establishment of another environmental campaigning organisation in America, the Wilderness Society. "The Wilderness Society was incorporated on January 21, 1935 by a group of eight men who would later become some of the 20th Century's most prominent conservationists including Aldo Leopold: noted wildlife ecologist and later author of A Sand County Almanac. The Wilderness Act, considered one of America's bedrock conservation laws, was written by The Wilderness Society's former Executive Director Howard Zahniser. Passed by Congress in 1964, the Wilderness Act created the National Wilderness Preservation System, which now protects nearly 110 million acres of designated wilderness areas throughout the United States. One of The Wilderness Society’s specialties is creating coalitions consisting of environmental groups, as well as representatives of sportsmen, ranchers, scientists, business owners, and others. It states that it bases its work in science and economic analysis, often enabling conservationists to strengthen the case for land protection by documenting potential scientific and economic dividends. The Wilderness Society played a major role in passage of the following bills:

Wilderness Act (1964)

Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (1968)

National Trails System Act (1968)

National Forest Management Act (1976)

Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (1980)

Tongass Timber Reform Act (1990)

California Desert Protection Act (1994)

National Wildlife Refuge System Improvement Act (1997)

The Public Lands Omnibus Act (2009), which added wilderness areas in nine states to the wilderness system. " (Wikipedia)

Lake Washington Story

Introduction

Chapter One: From the King County website

Chapter Two: Battle to Save Lake Washington - an outline by J T Lehman

Chapter Three: Lake Washington Case Study - J T Lehman

Chapter Four: The Uses of Ecology, Lake Washington and beyond, by W T Edmondson

Chapter Five: The Story of Metro, by Bob Lane

Chapter Six: Will the next Jim Ellis please step forward? by Thanh Tan

Chapter Seven: Lake Washington today, back to King County website

The work of the Wilderness Society has much in common with the campaigns at Lake Washington and Lake Annecy. Both worked to protect the unspoilt beauty of the natural world. Both served as paradigms of enlightened civic action involving developing a broad base of support amongst the public and using science both to inform, educate and convince members of the public. And both have led to significant practical improvement in the environment. However, as with their mentor John Muir, the first campaigns of the Wilderness Society were around the sole issue (crucial though it is) of protecting areas of natural beauty and the ensuing legislative successes of the Wilderness Society listed above came after the Lake Annecy and Lake Washington campaigns.

Interestingly, "the father of Earth Day, Gaylord Nelson is a former Wilderness Society board member and counselor. (Wilderness Society website) "He served three consecutive terms as a senator from 1963 to 1981. In 1963 he convinced President John F. Kennedy to take a national speaking tour to discuss conservation issues. Senator Nelson founded Earth Day, which began as a teach-in about environmental issues on April 22, 1970." (Wikipedia). Also around the time of the founding of Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace, "in 1969 at a UNESCO Conference in San Francisco, peace activist John McConnell proposed a day to honor the Earth and the concept of peace, to first be celebrated on March 21, 1970, the first day of spring in the northern hemisphere. This day of nature's equipoise was later sanctioned in a proclamation written by McConnell and signed by Secretary General U Thant at the United Nations. A month later a separate Earth Day was founded by United States Senator Gaylord Nelson. Nelson was later awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom award in recognition of his work. While this April 22 Earth Day was focused on the United States, an organization launched by Denis Hayes, who was the original national coordinator in 1970, took it international in 1990 and organized events in 141 nations. Numerous communities celebrate Earth Week, an entire week of activities focused on the environmental issues that the world faces. The first Earth Day celebrations took place in two thousand colleges and universities, roughly ten thousand primary and secondary schools, and hundreds of communities across the United States. More importantly, it "brought 20 million Americans out into the spring sunshine for peaceful demonstrations in favor of environmental reform." It now is observed in 192 countries, and coordinated by the nonprofit Earth Day Network, chaired by the first Earth Day 1970 organizer Denis Hayes, according to whom Earth Day is now "the largest secular holiday in the world, celebrated by more than a billion people every year." (Wikipedia) Earth Day, like Lakes Washington and Annecy, began as an effort to educate the public about environmental issues, but it took place more than a decade after the lake campaigns.

Lake Washington Story

Introduction

Chapter One: From the King County website

Chapter Two: Battle to Save Lake Washington - an outline by J T Lehman

Chapter Three: Lake Washington Case Study - J T Lehman

Chapter Four: The Uses of Ecology, Lake Washington and beyond, by W T Edmondson

Chapter Five: The Story of Metro, by Bob Lane

Chapter Six: Will the next Jim Ellis please step forward? by Thanh Tan

Chapter Seven: Lake Washington today, back to King County website

Another celebrated campaign which preceded our story was "a notable act of wilful trespass by ramblers, undertaken at Kinder Scout, in the Peak District of Derbyshire, England, on 24 April 1932, to highlight the fact that walkers in England and Wales were denied access to areas of open country. The mass trespass marked the beginning of a media campaign by The Ramblers' Association, culminating in the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000, which legislates rights to walk on mapped access land. According to the Kinder Trespass website, this act of civil disobedience was one of the most successful in British history." (Wikipedia). But again, this campaign addressed just one issue (crucial though it was): securing access to areas of natural beauty.

And finally, the first ever environmental campaign, according to the historian Harriet Ritvo in her book "The Dawn of Green", was that at Thirlmere in England in the late nineteenth century. Manchester’s ambitious civic leaders decided to turn Thirlmire lake into a reservoir to supply drinking water to the city’s rapidly growing population. This involved a complex engineering project requiring the construction of a 50 mile pipeline. In opposition, a campaign arose led by an assortment of Lake District citizens, academics, artists and intellectuals from across the country, invoking an unprecedented claim - that the beauty of Lake Thirlmere belonged to all citizens of England, not just local landowners, and should not be damaged for the benefit of one particular town. The campaign was a failure and the reservoir project went ahead successfully, although after significant delay and additional expense. The parallels with our story are many. Thirlmere was a campaign to safeguard a lake, set in beautiful, mountainous landscape; it involved a large-scale engineering project; it concerned the pressing need to secure clean drinking water supplies to a growing population; and it used the argument that the beauty of nature should be preserved for all to enjoy, including future generations. But the differences are even more striking. The stories of Lakes Washington and Annecy turn out to be in direct contrast to that of Lake Thirlmere. These lake campaigns were not to prevent a large engineering project from taking place and damaging the environment but on the contrary to undertake such a project to protect the environment. The initiative to take action to secure the supply of clean drinking water came not from a big municipal local authority but from local citizens. The campaigns were entirely locally organised and not reliant on support from a diverse group of activists from across America or France. And last, and certainly not least, the campaigns were demonstrably successful. Rather than being the dismal cautionary tale to all environmentalists portrayed in Ritvo’s account of Thirlmere, they are fine examples of successful environmental campaigns to he held up as an inspiration to others. It is in this context that it is asserted that Lake Washington and Lake Annecy represent the first significant, successful, comprehensive environmental campaigns in history.

Lake Washington Story

Introduction

Chapter One: From the King County website

Chapter Two: Battle to Save Lake Washington - an outline by J T Lehman

Chapter Three: Lake Washington Case Study - J T Lehman

Chapter Four: The Uses of Ecology, Lake Washington and beyond, by W T Edmondson

Chapter Five: The Story of Metro, by Bob Lane

Chapter Six: Will the next Jim Ellis please step forward? by Thanh Tan

Chapter Seven: Lake Washington today, back to King County website